Slow Space: Good Design Principles

At Aamodt / Plumb we strive to create good buildings, which we define as empathetic, experiential, beautiful, and connected to nature. We manifest these core ideas of good buildings in the following design principles.

Slow Space: 8 Principles of Good Design

1 NATURAL MATERIALS IN THEIR WHOLE, RAW AND AUTHENTIC FORM

We choose to elevate humble, timeless, local materials over the elite, new, and precious. We celebrate the intrinsic qualities of materials, including the idiosyncrasies and perceived imperfections, which make them unique and beautiful. Far from representing disorder, these qualities represent another higher order of a natural world that is constantly in flux.

2 TRACES OF TIME

We celebrate time in the marks left by the process of making, weathering and use (and by observing something closely). Nature and weather are dynamic, unstable, and unpredictable, as seen from the deserts in North Africa to rainforests in Brazil to volcanoes in Japan. In Norway the word for weather is “vær” and the verb “å være” means “to be.”

Therefore the whole notion of existence there is “to be in a changing, shifting, unpredictable world.” In Buddhism this observation equates to the concepts of ephemerality, transience, and impermanence in life. Buddhists believe we have more than one life on Earth so there is time enough to slow down and observe all the details.

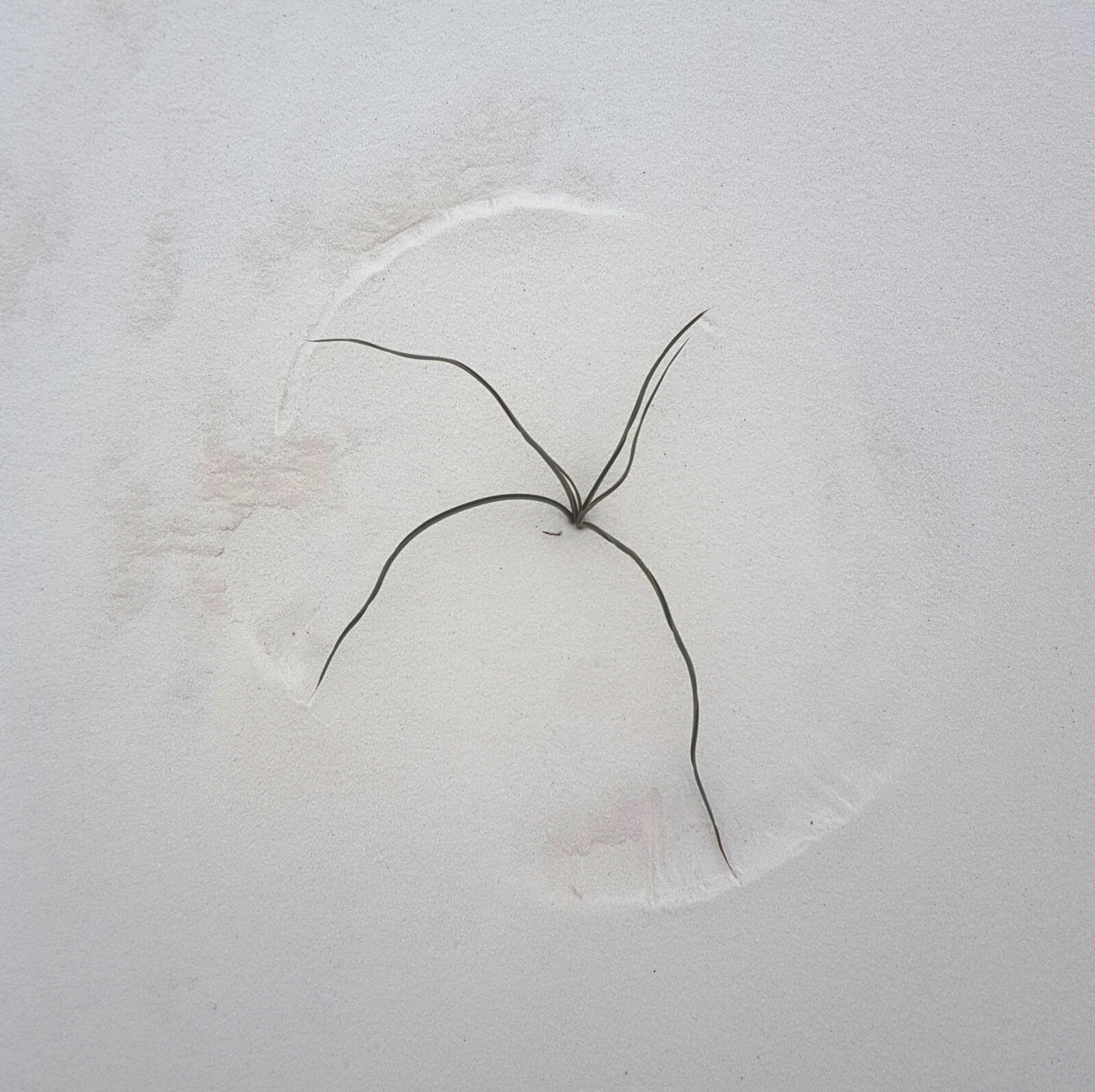

3 SOFT EDGES AND BLURRED BOUNDARIES EXPERIENCED THROUGH MOVEMENT

In the nordics for half of the year there is continuous twilight where the sun’s oblique angles create a moody, shifting light. The light creates space that has no distinct boundary or clear form. Nothing is in sharp relief. Nothing feels permanent. Everything is changing and experiential.

So too with the Japanese wabi-sabi aesthetic where things “have a vague, blurry or attenuated quality – as things do as they approach nothingness (or come out of it).” These soft edges must be experienced through proprioception, our body’s movement through space, sometimes referred to as the sixth sense.

4 MUTED PALETTE OF MATERIALS, COLORS AND LIGHT THAT SOOTHE THE MIND AND BODY

Natural materials, earth tones, and the colors of the sky at dawn and dusk are both familiar and achingly beautiful. They complement and balance each other and create a neutral and inclusive environment that everyone can relate to and customize in their own way. This is an easy way to bring the calming effects of nature into the home.

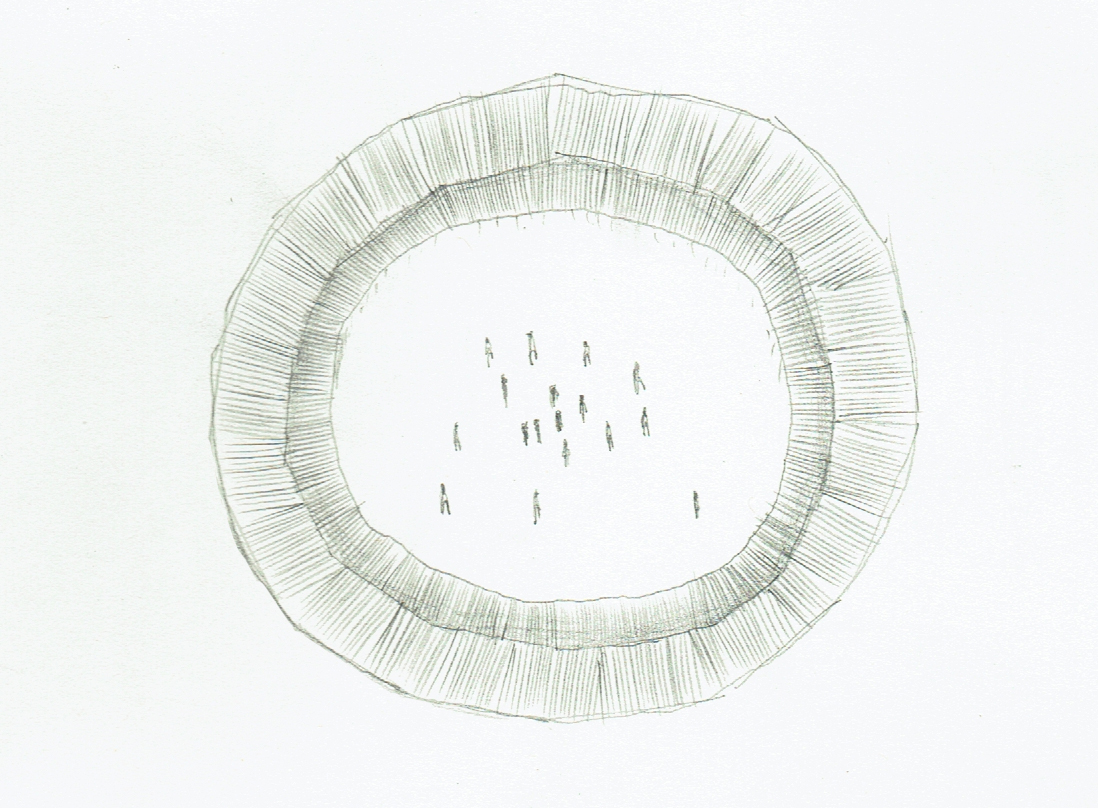

5 INTIMATE SPACES FOR INTROSPECTION, TO CONNECT WITH ONESELF AND OTHERS

The word “room” evolved from the Norwegian word “rydning,” which means clearing. Space, therefore, is a clearing in the forest, an aperture in nature that humans have created and where they live, and an intimate space is one that prioritizes the individual.

The Japanese metaphor of space as a bowl, a fluid circular shape to be filled with possibilities, is also an intimate space, focused inward to “enhance one’s capacity for metaphysical musings.”

Many African cultures use circles to represent the interconnectivity of all aspects of one’s being, including the connection with the natural world. African circle dances reflect another form of intimacy through community, unity, and inclusion.

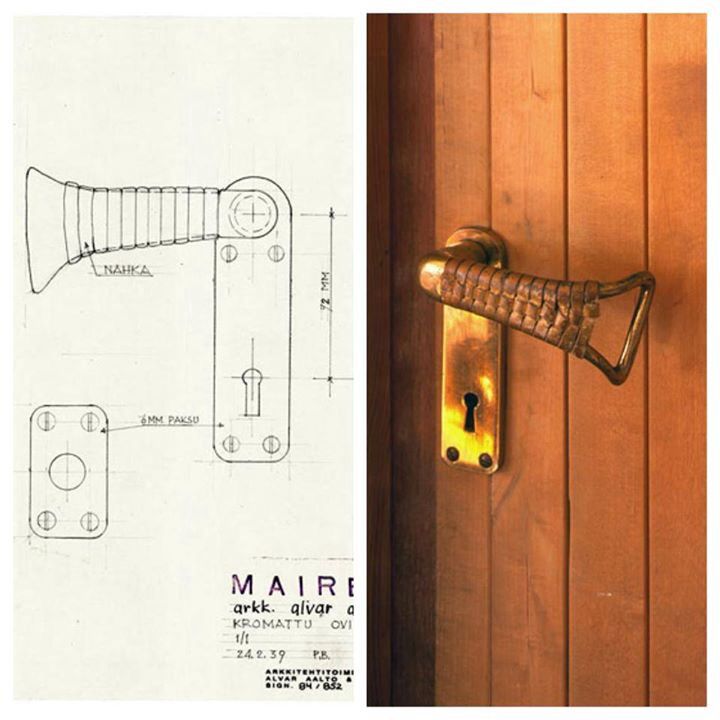

6 SENSORY DETAILS THAT AROUSE ALL MODES OF HUMAN PERCEPTION

We perceive the world with all of our senses: sight, sound, smell, taste, touch, and movement. Instances where one comes in contact with the building, like the door handle at Villa Mairea by Alvar Aalto, are opportunities for deep sensory connection. This is also true in wabi-sabi, where things “beckon: get close, touch, [and] relate. They inspire a reduction in the psychic distance between one thing and another, between people and things.”

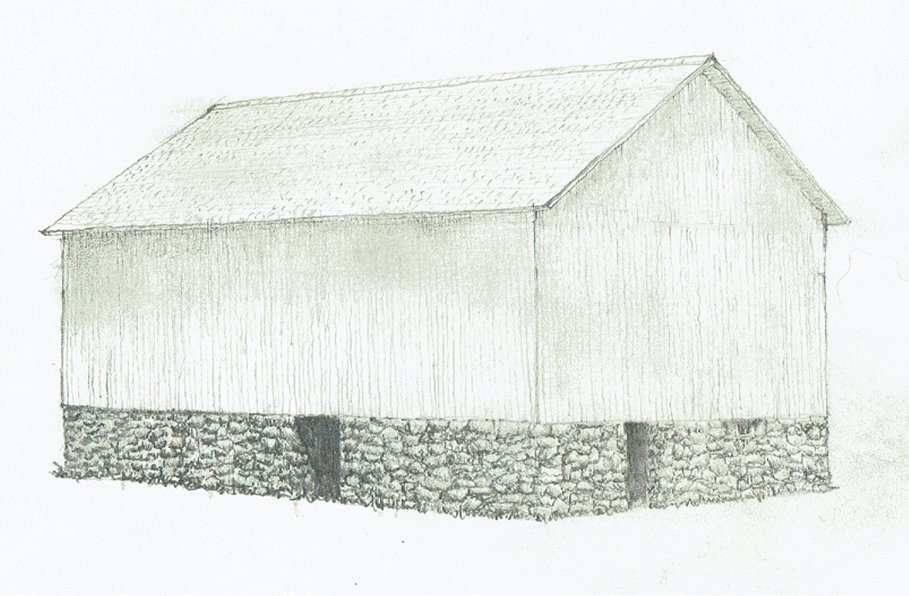

7 SIMPLE FORMS EXPRESSING AN ECONOMY OF MEANS, GRACEFULLY AND WITHOUT PRETENSE

Folkcraft, indigenous, and vernacular buildings such as barns, smoke houses, longhouses, and yurts are both efficient and poetic. The form of these structures has evolved over time and bears the wisdom of culture and experience.

8 COEXIST INTENTIONALLY

We promote purposeful, intimate, and ethical interactions between citizens, where the architecture focuses on people, rather than the building itself. In Japan, wabi-sabi principles suggest that no one thing should be more important than another and buildings should coexist easily with their context.

In the Nordic Region this goes further to say no person should be more important than any other and all people are equal. This social responsibility is evident in the humanism of Nordic Design and our work at Aamodt / Plumb.

These 8 Principles of Good Design are derived from our belief that good, clean and fair housing is a human right. Read our article, SLOW SPACE: GOOD, CLEAN AND FAIR ARCHITECTURE AND CONSTRUCTION, to learn why we created the Slow Space movement and made it our mission to create homes that are good, clean and fair.